Why Projects Fail in Production

Most software projects don’t fail because of bad code. They fail because teams never aligned on an explicit definition of “done.”

You’ve seen the pattern. A team ships an AI feature that looks brilliant in a demo but degrades under real traffic and variance. An automation workflow handles the happy path, then produces invalid outputs as soon as edge cases appear. A machine learning model posts strong benchmark scores, then confuses users with inconsistent behavior in production.

The instinct is to blame execution—the team moved too fast, the model needs more data, the prompts weren’t refined enough. But these are signals, not root causes. The real failure happened earlier: teams assumed they shared the same expectations without turning them into a measurable contract.

This is the gap spec-driven development addresses directly.

What Spec-Driven Development Actually Means

A specification isn’t a requirements document that collects dust in Confluence. It’s a behavioral contract: a clear definition of how a system should behave under defined conditions—including the conditions where things go wrong.

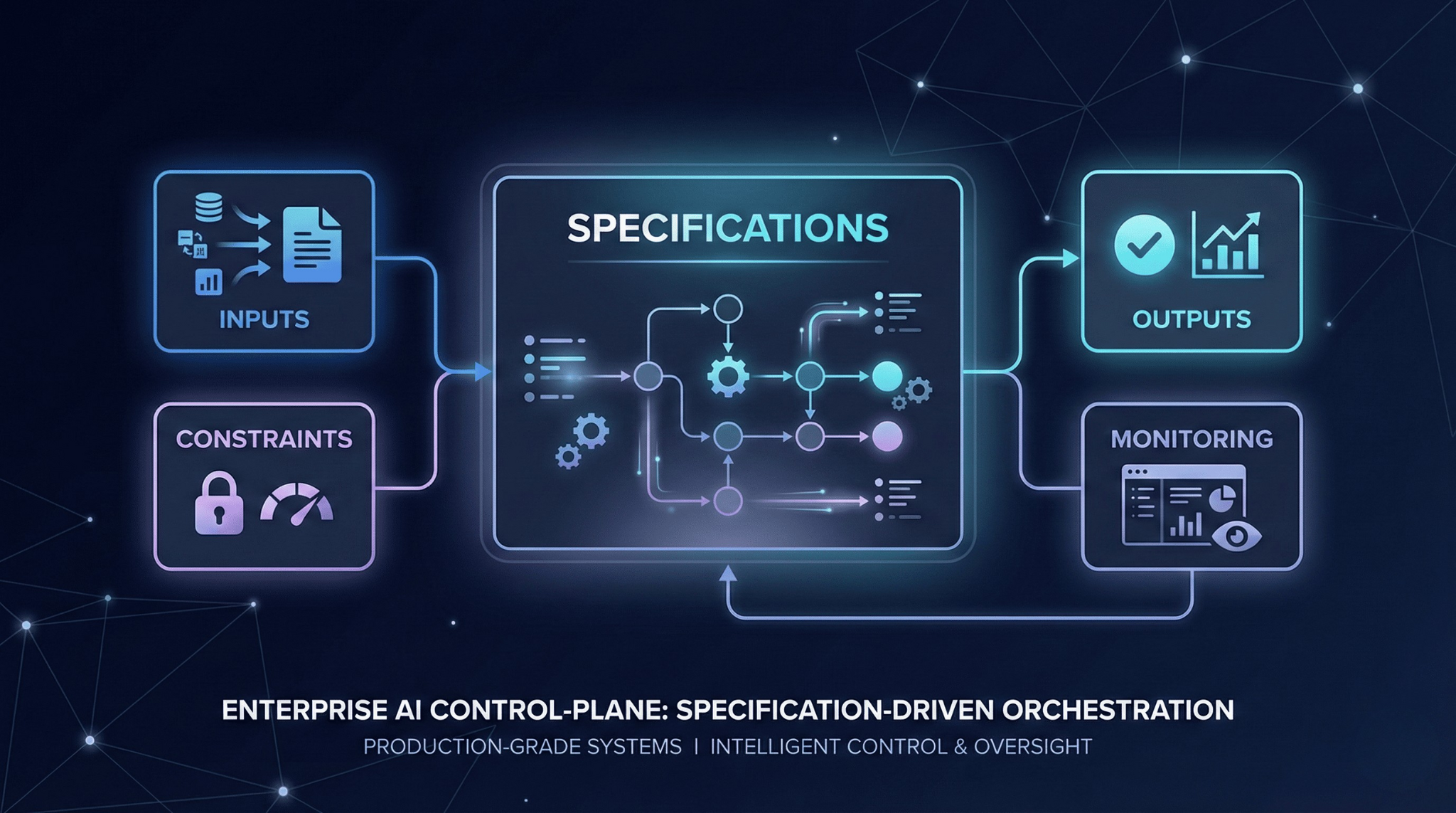

A useful spec makes four contracts explicit:

Inputs: what the system accepts, plus the assumptions and quality expectations attached to those inputs

Outputs: what the system produces, including format and quality standards

Constraints: the operating envelope (latency, cost, accuracy, compliance, safety)

Failure modes: what the system does when it cannot meet expectations (fallbacks, escalation, errors)

This differs fundamentally from code-driven development, where implementation becomes the de facto spec, and from prompt-driven development, where behavior emerges through trial-and-error rather than intentional design.

Why AI Systems Demand Spec-Driven Thinking

Traditional systems are largely deterministic at the interface level: given the same inputs, you can expect the same outputs and write tests with crisp pass/fail outcomes.

AI systems don’t behave that way. Output variance is inherent—and that makes specifications more critical, not less.

Ambiguity isn’t an edge case

When you build a classifier or an LLM-powered agent, the boundary between correct and incorrect behavior is often fuzzy. Without a spec that defines acceptable variation, teams end up in recurring debates about whether a particular output is “good enough.” Those debates slow development and create friction between engineering, product, and stakeholders.

Evaluation must be a contract, not a feeling

Evaluation is where many AI efforts quietly stall. Teams run a handful of examples, do informal spot-checks, and move on. That can work early—but it doesn’t scale.

A production-ready spec turns evaluation into an explicit contract: target thresholds, acceptable variance, latency and cost budgets, and compliance boundaries. It also defines the evaluation harness—what test sets matter, how regression is detected, and what constitutes a release blocker.

With that in place, optimization stops being subjective. It becomes measurable iteration: improve the metric, stay within constraints, and preserve behavior that users rely on.

Operational complexity multiplies the cost of missing specs

AI systems require monitoring that traditional software often doesn’t: drift detection, output-quality sampling, guardrail triggers, and fallback escalation. Without a spec defining expected behavior, it’s hard to build alerting that distinguishes between normal variation and real degradation.

Teams that skip specs and “just iterate prompts” eventually hit a wall. They accumulate incremental prompt tweaks to patch specific failures without coherent logic. They lose track of which behaviors are intentional versus accidental. New team members struggle to ramp up because tribal knowledge replaces an explicit contract.

The Anatomy of a Good Spec

Effective specifications share a common structure whether they describe a REST API, a data pipeline, or an AI agent.

Inputs

Inputs must be defined with constraints and assumptions. For AI systems, that includes not only data formats but data quality expectations:

What happens when input text contains typos?

When images are low resolution?

When structured data has missing fields?

Outputs

Outputs need both format definitions and quality standards. For example, an LLM system might specify that responses:

must be under 200 words,

must not include prohibited phrases,

must cite sources when making factual claims,

must return a machine-readable schema when downstream systems depend on it.

Constraints

Constraints establish the operating envelope: maximum latency, cost per request, minimum accuracy on held-out test sets, and compliance with specific requirements.

Failure modes and fallbacks

Failure modes deserve particular attention. Every production system encounters cases it can’t handle gracefully. A spec should define fallback behavior explicitly—return a default response, escalate to a human, or fail with a specific error code. Undefined failure modes don’t stay undefined; they become production incidents.

A short example (abbreviated spec)

To make this concrete, here’s an example of a minimal spec for an LLM-based email triage workflow:

Input: inbound email text + sender metadata; reject if subject/body missing

Output: JSON

{category, priority, summary, suggested_action}Constraints: p95 latency < 2.5s; cost < $0.01/email; no PII in logs

Quality: summary ≤ 60 words; action must reference a policy ID when applicable

Failure mode: if confidence < 0.65 → route to human queue with “needs review”

This level of specificity is often enough to align teams, define tests, and build monitoring.

Specs Are How Teams Iterate Faster Safely

Engineering leaders sometimes resist spec-driven development because it sounds like waterfall: months of documentation before writing code. That’s not what this is.

A spec is a hypothesis about system behavior. You write it before building, then revise it as you learn. Specs make iteration faster because they clarify what you’re testing. Instead of asking, “does this feel right?” you ask, “does this meet the acceptance criteria we defined?” The former invites endless discussion; the latter produces clear decisions.

Teams practicing spec-driven development often ship faster than those who don’t—not because they write more docs, but because they spend less time revisiting decisions that should have been settled early.

Applying Specs to AI Agents and Automation

These principles become practical when applied to real systems.

An AI agent handling customer inquiries needs a spec defining:

which query types it can handle autonomously vs. escalate,

what data it is authorized to access,

how it responds when uncertain,

and what success metrics determine whether it is performing adequately.

An automation workflow processing documents needs specs for:

acceptable input quality,

transformation rules including edge cases,

validation checks before outputs are committed,

rollback procedures when validation fails.

Specs don’t guarantee perfect systems. They guarantee that teams agree on what they’re building—and can measure whether they built it.

The Foundation for Systems That Actually Scale

Spec-driven development isn’t bureaucracy. It’s operational clarity. For AI systems, it’s the difference between outputs that look good and behavior you can trust under real traffic, real cost constraints, and real failure modes.

The teams that scale aren’t the ones that iterate the fastest in demos. They’re the ones that define behavior precisely enough to test, monitor, and evolve safely. Models will change. Tooling will evolve. But clear contracts—inputs, outputs, constraints, and fallbacks—remain the foundation for systems that actually scale.